Lone Wolf and Cub and Action without Words

In the book of Acts, the disciples of Jesus are gifted with the Holy Spirit after his ascension. One metaphysical, supernatural, or even magical gift of the Holy Spirit was that the disciples were able to go out into the city of Jerusalem, full of people from across the Roman Empire, and speak in a way that everyone heard the words in their own native language. Unlike modern glossolalia, it seems almost as if the disciples could speak a universal language. While I don’t think the disciples were drawing pictures, I do think comics are a similar universal language.

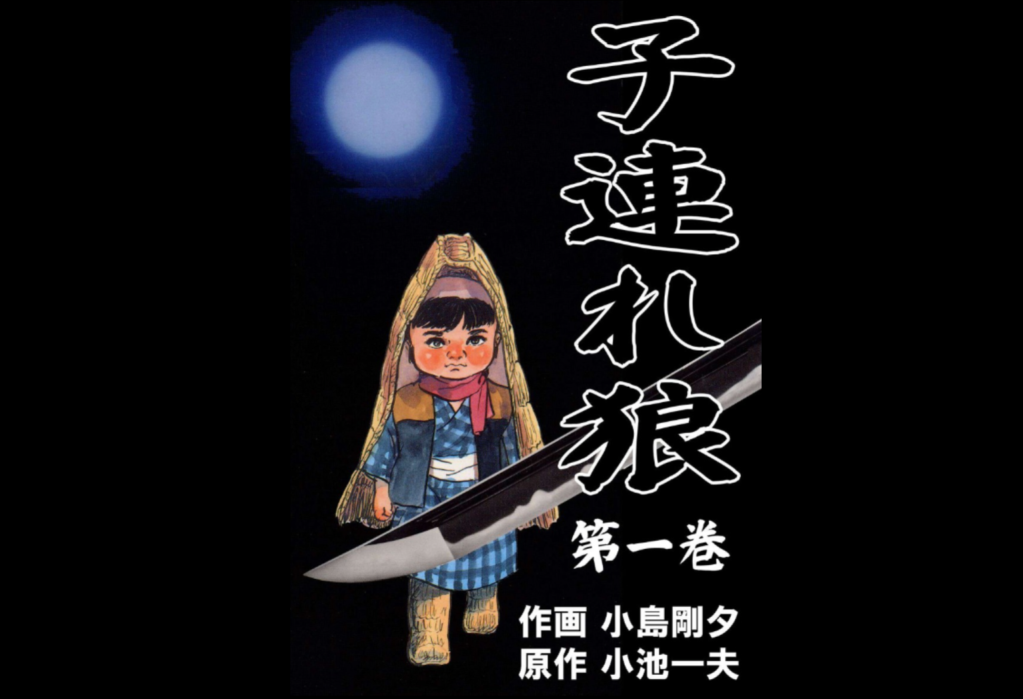

A truism in comics is that the best pages of comics work so well visually that a reader can understand what is happening without any of the words. Like an Ikea instruction manual, the drawings are so precise and in just the right order that they can be read across cultures. But, I wanted to test this. I figured, one of the best possible test cases would be Lone Wolf and Cub, written by Kazuo Koike and artist Goseki Kojim. In addition to being one of the most influential manga of all time, it inspired Frank Miller’s Ronin, four years before it was translated to English. My case, in essence, is already made. But let’s walk through a sequence from the first issue of the original Japanese version. Remember, this is read from right to left, opposite Western comics. What can I get out of this without being able to read any dialog or captions?

We start with a scene-setting montage. This is a common cinematic technique. It introduces a rhythm to the narrative, while also implying an indeterminate amount of time before the action. We don’t know how long this baby cart has been pushed by our protagonist, who we haven’t even met yet. It also introduces some of the iconography of the story: the banner, the baby cart, and the baby itself. This last point is key. Without showing us the baby, it can be easy to forget the stakes here. Our hero isn’t just fighting for himself, but for a helpless child. We don’t yet get a drawing of the protagonist. That retains an air of mystery and intrigue. If you haven’t watched Raiders of the Last Arc recently, for example, Spielberg does something similar. We see Indiana Jones in silhouette, his hat and his whip, but we don’t actually see Harrison Ford’s face for a long time.

Obviously, these men are antagonists. The non-literal red background and hats that obscure their faces in shadow make that clear. They are all looking at the same thing. The second panel is the baby cart, which, because of the Kuleshov effect, our brains interpret that as what the men in hats were looking at in the panel before. Panel 3 is the reveal of our protagonist’s face. It is actually the first time in the whole series that we see him. His brow is furrowed and the markings around his face imply he is turning around to see these men. He knows that the men in hats are shifty. The final panel shows them surrounding him. Although they exchange words, the reader is meant to feel on edge.

Although the previous page has put the reader on edge, the tension seems to abate at the start of this page. The men in hats seem to be smiling, and their panel isn’t soaked in shadows or a red background. Our protagonist is smiling too, happy to show the men his baby.

Suddenly, something happens. The hats are all midair. The men aren’t drawn tossing them up, that action happening entirely between panels. It is a little surprising at first, feeling like a non-sequitur from the panel before. This shock is the point. It is a sudden change of mood, from the relaxed showing off of a child to the moment of action. This is confirmed in the next panel, again drawn with a red background. The comic has already primed the reader to associate red with danger, and when the villains are drawing swords, that makes sense. This panel makes the previous potentially confusing non-sequitur make sense, resolving a mini-mystery.

This page concludes with a wide shot looking down towards the characters. The villains are ready to fight, hands at the ready, while the lead looks almost relaxed, standing at the baby cart. He hasn’t even begun to put his hand on a weapon, and that’s if he even has one. For all the reader knows at this point, he could just be a defenseless man. The tension and anticipation of the incoming action has been building for multiple pages now, but no action has commenced yet. As a reader, you are ready to go.

Even as the action starts, however, the tension is not fully released. Our protagonist looks on with anger in his eyes. It is obvious he knows what is coming. His eyebrows are low, and his face tilted forward, with a gruff smile. All of this communicates his seriousness. His enemies have their hands on their swords, not yet drawn but ready at a moment’s notice. Finally, they attack. For the first time, things aren’t immediately clear, but that’s intentional. This panel feature features a bust and a hand, disconnected from the rest of their body, a person in shadows, and an abundance of speed lines.

In the next panel, however, the speed lines are gone. This feels almost like a freeze-frame. The color drops out and there are horizontal lines running across, like a VHS tape. I’ve just dated myself, but let’s keep going. We can see our protagonist is finally moving, but it seems too late. The villainous men are practically upon him. There is a final reminder of the stakes, the baby in the cart. Our protagonist finally draws his sword and the page is done. We’re so close to actually getting some action. Drawing out the setup is a common technique in horror comics, but it also works here.

And it’s over before it started. The previous page ended with the setup, and this page begins immediately following the action, a classic setup-reaction formula of action comics. Our protagonist has attacked, indicated by the speed lines, the sound effects, and the two white “bursts” to indicate where contact was made. Only, instead of showing us what happened, the next three panels show three metal chunks flying through the sky. Before you can even figure out what happened, our protagonist jumps up and lands on the baby cart, another example of setup-reaction comicbooking. Finally, the last panel answers the “mystery”. The villains hold up their swords, now with tips broken off. That was what we saw flying away in the three middle panels.

The action sequence continues, and I could as well, but I figure I’ll stop here. Clearly, the experiment was a success. While I’m sure there was some nuance that I could have gained if I understood the conversation had between our lead and the three ninjas, overall the whole sequence was very understandable. By sticking with the basic rules of comic books, Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojim create action sequences that work across language barriers. You can try this yourself! There are plenty of comics made in Japan, Europe, and across the world. See what you can get from a few pages without being able to understand the written words. This will help you gain further knowledge on your journey of Divining Comics.

If you haven’t already, consider supporting this work at ko-fi.com/spikestonehand. There, you can leave a tip or buy Zine versions of these articles. Doing this helps keep the website going. Follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Leave a comment