How a comic can depict multiple layers of performance, deception, and reality

What is truth? Any magician knows that reality is malleable. The things that you think you see, know, or remember aren’t always accurate. A skilled magician can use the power of performance to manipulate your perception. They might dress up in outfits they wouldn’t normally wear, and use props and magic words, to give their performance power. Art is the same way. All art is in part a performance, and comics are no different. The sequences of drawings are the magicians tools, enhancing the story told. Follow the artist’s hands, and learn just how the magic is done.

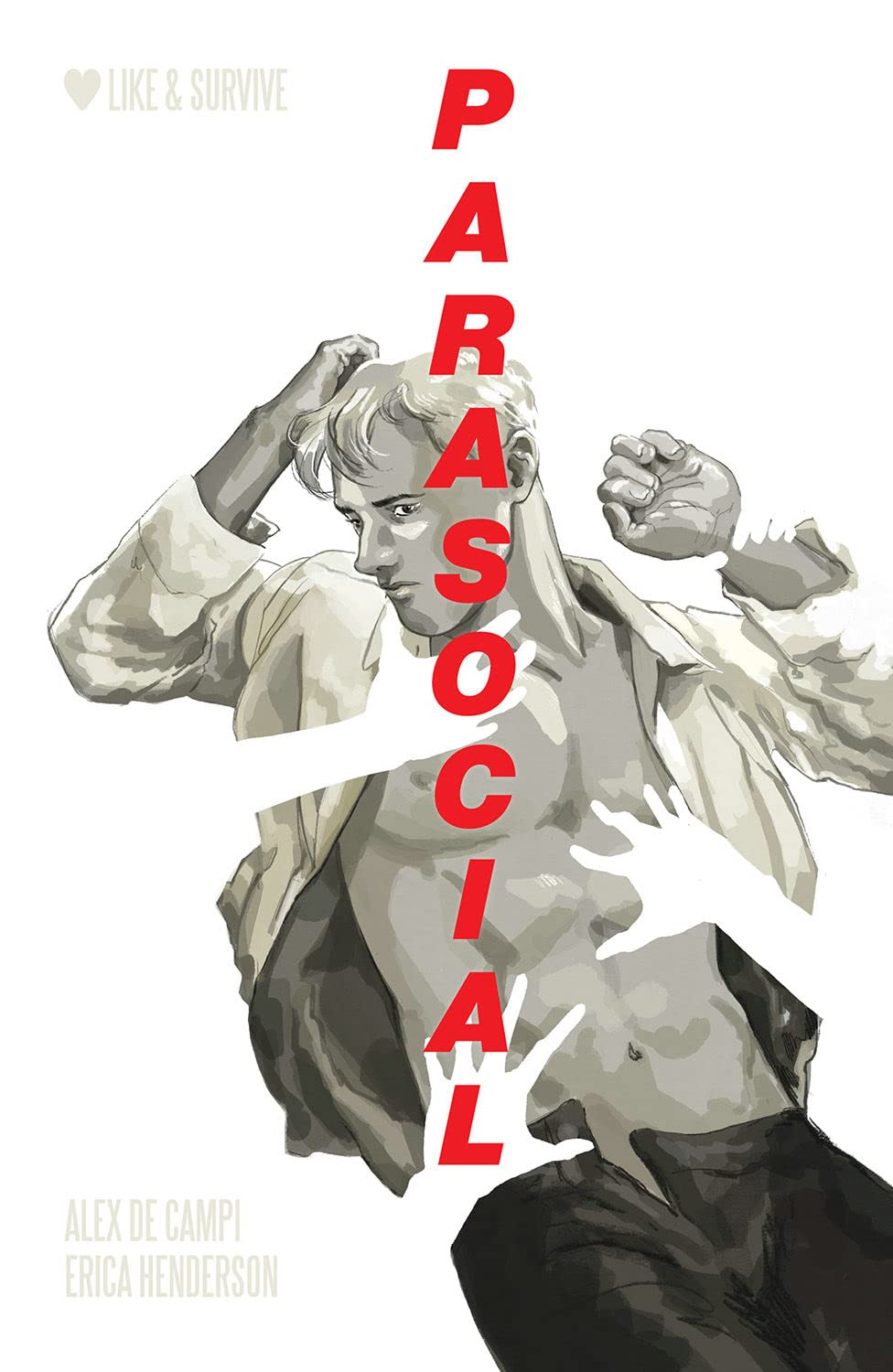

Parasocial is the second graphic novel collaboration between writer Alex de Campi and artist Erica Henderson. The pitch is straightforward enough: Misery for the SuperWhoLock generation. Luke Indiana, an aging genre TV heartthrob, is kidnapped by a deranged fan named Lily. He has to now give the performance of a lifetime to escape. But, is that all that’s going on? First, I will demonstrate how the comic repeatedly undermines the performative fantasy with the harshness of reality. Then, I’ll upturn everything you believe in with a mind-blowing theory as to what’s really going on. Spoilers to follow.

From the very beginning, the major theme of performance is highlighted. A group chat of Luke Indiana fans share a Cameo he made for one of them. For those of you that don’t know, Cameo is a service where fans can pay celebrities to make a short video. Instead of seeing famous people acting on the silver screen, they get to see their real life on the cell phone screen. Only, Cameo isn’t access to their unvarnished truth. It’s another avenue of performance, and the better the celebrity is at convincing fans that they aren’t acting, the more money they can make.

When Luke Indiana is on, he is on. He’s charming, self-effacing, and sincere. He doesn’t re-take the video after his kid interrupts him because that adds to the verisimilitude and his good-guy image. Lily and her friends in the group chat, as far as we can tell, don’t seem cognizant that this is just another performance. They talk about him the same way you might talk about a character on a TV show. In a certain sense, that is what he is. In addition to the role of X-9 on Rogue Nebula, he plays the role of Luke Indiana. Later on in the story, it’s revealed that Luke Indiana is a stage name that he took on, further cementing this gap between performance and reality.

On the very next page, we meet the real Luke. He’s alone in his car, parked in a garage before a convention appearance. His head is buried in his hands, and he has to psych himself up before going out. The contrast between the Luke here and the Luke on Cameo could not be clearer. There is no one for him to perform to, so he doesn’t feel bad about expressing his negative feelings. By opening the book with these two scenes, de Campi and Henderson are priming the readers to question the nature of performance and what reality even is.

During the convention, this theme develops through the use of flashbacks. I’m going to talk about them in reverse chronological order. Each depicts a different type of performance Luke is giving, and, if we read the art of acting uncharitably, a different target for deception. By thinking through who the audience is, who Luke is, what the nature of the lie is, and why he is lying, we get a glimpse into the nature of performance.

During a large group Question and Answer, a fan asks Luke what upcoming projects he has. While the flashback reveals that the answer is “not much,” Luke can spin things into a PR approved “watch this space”. But Luke isn’t just telling this to a devoted fan. This is a junket at a convention. There is a large crowd within the room. Beyond that, there are almost certainly journalists for geek culture websites in attendance, eager to break a scoop. Luke is performing here for the entire internet. He’s also performing for potential employers. His answers here have to be kept vague because anything he says has the potential to blow up.

Earlier, Luke and Lily interact at his booth, though he has no idea of what is to come between them. She thinks she recognizes his shirt, but a flashback reveals that it can’t have been the same shirt as before because his clothes are at his ex-wife’s house. This lie is smaller than before because his audience is too. No journalist is going to report that Luke Indiana wore the same shirt twice, but they might report about his divorce. He, reasonably, wants to keep that information private. So Luke tells a small white lie, believable and based enough in the truth. This performance isn’t for any more nefarious of a purpose than getting through a persistent fan’s grilling.

Finally, Luke’s first revealing flashback is from before he gets to the booth. He approaches a former costar and acts friendly with her, insisting that it was a shame that her character was killed off. However, the flashback tells a different story. Without ever detailing why, it reveals that this costar was actually written off at the insistence of Luke because his “wife is freaking out.” The implication is presumably that something sexual happened between the two of them, and Luke’s wife found out.

But, in this instance, who is Luke lying for? What was his performance? It certainly isn’t for the costar. Her face and utter lack of response to him shows how uncomfortable Luke makes her. There doesn’t seem to be any fans listening in. So again, who is Luke performing for? The only possible answer at this point in the narrative is that he is lying to himself. He wants to think of himself as a good person. So, he pretends like this instance of him getting someone he was intimate with fired never happened. The nature of performance is complicated, and the “truth” or even the reality of a situation is almost always a complicated question involving differences of perspective.

Contrasted with the three performances at the convention, Luke tells Lily three different stories after she kidnaps him. From one story to the next, Luke himself changes. Each time, he grows more honest. At the same time, he is still performing. Sure, he’s doing so with the purpose of escaping with his life intact. But, even as the “truthiness” he is conveying goes up, he can’t escape his ulterior motives.

Luke’s first performance, his most dishonest, is a play at Lily’s physical desires. He compliments her, lies about remembering her, and asks if she wants to be his girlfriend. This catches her off guard, and she does release him. When they go in for a kiss, Luke surprises her by hitting her. She can recapture him at this point by stabbing him, and he can’t pull that performance off again.

Basically, nothing that Luke says at this point comes from a place of truth. Perhaps he is bad with names, and he might find Lily attractive. But he obviously does not want to be in a relationship with her. The fictional basis of his proposal is reflected in the art. It changes to look more like fan-art from tumblr. The reader “sees” his acting manifest in the artwork. But the fact that it is so noticeable as a performance keeps things from ever feeling real.

When Luke tells his next story, it is more honest. This time, he attempts to play Lily’s emotions instead of her desires. Lily sees a scar that she presumes is from an appendectomy. Luke reveals, however, that he got this scar from a drunken fall onto a fence, noting that he thought up his stage name, his first performance, in the hospital recovering. He concludes by pleading for his release, arguing that he can lie about the wounds Lily gave him, just like he lied about the “appendectomy” scar. Luke pleads that Lily not leave his kids fatherless, the appeal to her emotions.

That last comment is the most notable exaggeration of the truth. His divorce was already shown. His wife even commented that he’s basically merely a guest start in his children’s lives. While they certainly would miss their father if he was kidnapped and killed by an obsessive fan, Luke is almost certainly thinking mostly about himself in this situation, as would most reasonable people. While Lily doesn’t free him, she is convinced to let him up out of the basement. The second performance works at least as a stalling tactic, setting up his third story.

Luke’s final story is the most truthful. It is him baring his psyche to Lily, committing to genuine vulnerability. Thus, continuing the trend, this story is an appeal to Lily’s rationality. “I am a thinking human, just like you, and this isn’t how thinking humans treat one another.” Ultimately, this story is how he can escape.

He begins with a story of his grandmother, who was very sick as a child. The doctor recommends changing her name, so that the Angel of Death can’t find her. She survives, and Luke juxtaposes her story with his family’s name change at Ellis Island, his Hollywood stage name, and indeed, every acting job he had. Luke thought, maybe only subconsciously before this moment, that by adopting new personas, he could escape death forever. This isn’t just a story. Luke is baring his soul to Lily. He is explaining not only why he acts, but also the fundamental emptiness he feels. Everything that Luke is, that he pretends to be, isn’t to fool fans. His ultimate performance is trying to fool himself.

And yet, isn’t Luke still performing? Is he not still trying to elicit an emotional response from Lily? There is a post-structuralist point here, that all communication is to some extent a performance. When I am talking to you, I base what I say on who I think you are. That is inherently reductive because I almost certainly can’t know you as much as you know yourself. Then you, as a listener, do the same. You interpret my speech based off of the version of me you have in your head. This can iterate infinitely, as I consider how I think you’ll interpret my speech, and you take into account how you think I’ll adjust my speech based off of my prediction of your interpretation, and so on and so on.

By making Luke an actor, and in this scene an actor engaged in self-reflection on the nature of acting both on screen and as a public figure, the comic Parasocial draws the question of truth and performance to the surface. Earlier, in the basement, Luke offers his theory of the actor — fan social contract. “I pretend to be your friend…just like I pretend to be a robot assassin, or any other role. And in return, you pretend I’m a better person than I am.” Of course, this contract can never be spoken aloud, or the kayfabe is broken. And Lily’s actions are a result of what can happen when one party doesn’t understand the unspoken rules governing this arrangement. They think the performance is real, or, at least, convince themselves that it is.

The rest of the book continues. Lily, unable to see any other options that don’t end up with her in jail, attempts to burn her own house down with Luke still in it. He escapes, barely conscious, and is rescued by a family in a nearby house. In his semi-aware state, Luke has a vision of an angel, presumably the aforementioned angel of death. If the book ended here, it would be reasonable to assume Luke died. But, that isn’t how it ends, and there is one layer of performance left unexamined. Yes, it’s finally time to enter the Wild Fan Theory Zone!

Parasocial ends with two pages mimicking Luke’s Instagram, and a sole text from the fan group chat Lily was in. The first Instagram doesn’t offer us much, other than proof that Luke did indeed survive. It’s the second post where things get really interesting. Luke reveals that he is the author of Parasocial! The book cover on his post is identical to the one in our world, down even to the creator names. In the instagram post, Luke claims to have written it under a pseudonym, a funny touch.

Logically, we know this isn’t actually the same as our Parasocial. For one, his post says the book came out a week prior, which means the instagram couldn’t have been included in his version. We can also talk to Alex de Campi and Erica Henderson because they are real people. That means, in a certain sense, this book is Luke’s next performance, the new identity he took on.

But, let’s assume that much of the inside of Luke’s Parasocial is identical to our Parasocial. This is like how The Hobbit was written, in universe, by Bilbo, or that The Book of the New Sun was written by Severian. I use those two examples because they are famous for having unreliable narrators. Bilbo’s version of how he gets the ring from Gollum is revealed, in Lord of the Rings, to be untrue. This near-final page forces the reader to reconsider the context of everything prior. The entire graphic novel becomes another layer of Luke’s performance. He could, in the universe of the story, have changed all sorts of details as to what “actually” happened.

Which brings us to the final page of the narrative, the text from the fan group chat. “Have any of you heard from Lily recently? I’m worried about her.” We can assume, like the instagram post, that this text message wasn’t included in the version of Parasocial that Luke wrote. This is perhaps the only page of the book that escapes his performance. The first time I read this, it made me doubt everything I just read.

This text means that Lily is a real person, in the world of the book. Luke didn’t make her up whole-cloth. So, assuming there is some truth contained within, what can be verified to have occurred? Everything at the Convention would have had multiple corroborating witnesses. Then, at the end of the book, the family who saves Luke could also testify as to what really happened. That leaves a big chunk of the book where the only witnesses are Luke, Lily, and Lily’s grandmother, who is senile and often on Ketamine. If Luke wanted to lie about something, this chunk would be where he changes things up.

Is there any evidence that Luke changes things? The biggest point of data is that text implying Lily has gone missing. The last time we see her in the story, she sets her house on fire and leaves the narrative virtually unharmed. She doesn’t get arrested, and Luke doesn’t kill her. So why is she missing? Further, we know that Luke lies. He admits to a sustained lie about the origin of one of his scars. The flashbacks establish him as regularly lying to the public, and even himself. There is no reason to assume that in a book he is releasing for the public, he wouldn’t view the story as a performance, making himself look better than he actually is.

Is it possible that Luke killed Lily? Let’s examine the evidence that Lily gives us before she panics. The gatorade bottle has both of their fingerprints and also traces of ketamine. His skin and clothes left residue on the ropes. It seems entirely possible that Luke, a washed-up celebrity going through a divorce, might have had a drug-fueled romp with an over-eager fan that took a dark turn.

Or, with even less lying, perhaps everything happens as depicted up to the point where Luke hits Lily with a chair. She is shown bleeding and seemingly unconscious, lying on the floor. But, in her remaining appearances, she seems totally fine. She doesn’t seem to have a concussion, any broken bones, or even wounds to account for the pool of blood around her head. Luke could have accidentally killed Lily in self-defense here, panicked in his blood-deprived and hungover state, set her house on fire, and lied about Lily doing the arson to protect himself.

I don’t think there is any definitive proof as to what “actually” happened. This is a fictional story, and none of it actually happened. But, I think that questioning the narrative that Luke puts forward enhances the theme of performance, storytelling, and the parasocial relationships that creates. If you have any theories yourself, please share them. Thinking through the nature of truth in fiction and the idea of performance will hopefully help in your continuing journey of divining comics.

If you haven’t already, consider supporting this work at ko-fi.com/spikestonehand. There, you can leave a tip or buy Zine versions of these articles. Doing this helps keep the website going.

Leave a comment